For a long time, I had trouble getting into Elliott Smith's work with his previous band, Heatmiser. I don't know what I was hoping for, but it didn't quite scratch my itch for more Elliott Smith. Then, I finally made it to their last album, Mic City Sons, and I recognized the song "Half Right." It's a slightly jazzed up, full band version of my favorite sombre acoustic song on New Moon, the posthumous Elliott Smith rarities compilation. Through the Heatmiser albums, you can trace a transition from the more prevalent hard rock that was popular in the '90s to something more personal that would lead Elliott to his solo career. So I cobbled together Elliott's Heatmiser songs into a mixtape that could sound like an Elliott Smith album.

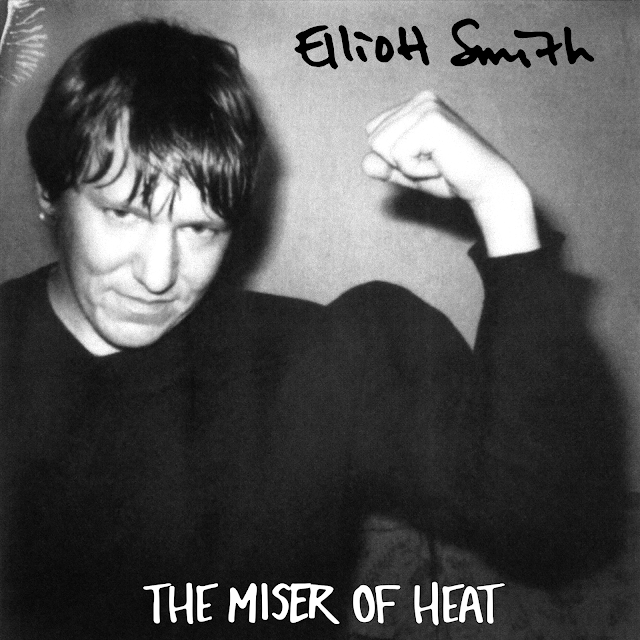

Elliott Smith - The Miser of Heat

| 1. Half Right | - Mic City Sons - 1996 |

| 2. Plainclothes Man | - Mic City Sons - 1996 |

| 3. Antonio Carlos Jobim |

- Cop and Speeder - 1994 (Bonus: Live solo acoustic version here) |

| 4. See You Later | - Mic City Sons - 1996 |

| 5. The Fix is In | - Mic City Sons - 1996 |

| 6. You Gotta Move | - Mic City Sons - 1996 |

| 7. I'm Over it Now |

- Live on KBOO - 10-25-1994 (Full set here) (Bonus: Live solo "Have You Seen Her?" version here) |

| 8. Something to Lose |

- Cop and Speeder - 1994 (Bonus: Live solo acoustic version here) |

| 9. Get Lucky |

- Mic City Sons - 1996 (Bonus: Live solo acoustic version here) |

| 10. Everybody Has It | - Everybody Has It Single - 1996 |

| 11. Idler | - Yellow No. 5 EP - 1995 |

| 12. Pop in G | - Mic City Sons - 1996 |

| 13. Christian Brothers | - Heaven Adores You Soundtrack - 2014 (Recorded 1995) |

(Lossless files are included where possible, other lossy formats remain

from their original leaks. All files are from original sources with no

transcoding or editing. Please do not transcode/convert or edit these

files when sharing.)

The Miser of Heat

and The Subliminal Conformity of Masculinity

If you only knew Elliott Smith from his solo work and then found out about Heatmiser, you might be surprised. The trajectory of his musical style from hardcore growler to spirited singer-songwriter is a revealing analogy for the subliminal influence of masculine conformity.

If you started a band in 1991, like Elliott did with Heatmiser, there was probably no way you could escape the wave of "grunge music" that was overtaking popular consciousness. 1991 was the year that Nirvana's Nevermind came out, as well as Pear Jam's Ten, Soundgarden's Badmotorfinger, not to mention other "but rock" offenders like Metallica's black album and Guns and Roses' Use Your Illusion. It would be even more difficult to distance yourself from this sound if your band was in Portland, Oregon, a few hundred miles from the grunge epicenter of Seattle, Washington.

If you started a band in 1991, like Elliott did with Heatmiser, there was probably no way you could escape the wave of "grunge music" that was overtaking popular consciousness. 1991 was the year that Nirvana's Nevermind came out, as well as Pear Jam's Ten, Soundgarden's Badmotorfinger, not to mention other "but rock" offenders like Metallica's black album and Guns and Roses' Use Your Illusion. It would be even more difficult to distance yourself from this sound if your band was in Portland, Oregon, a few hundred miles from the grunge epicenter of Seattle, Washington.

This is something that Elliott's friends say over and over again in the documentary Heaven Adores You, released in 2014. In an interview, Kill Rock Stars record label founder Slim Moon says, "indie rock was still coming out of the punk tradition, it was anti-a lot of the things the 70s had been known for, including heartfelt singer-songwriters." J.J. Gonson, Heatmiser manager and Elliott's once girlfriend, said, "It was embarrassing to be doing acoustic music. Nobody did it. Everybody was rough."

The sonic trends of the Portland music scene at the time are described in Heaven Adores You as "muscular," "loud," "angry," and "shouty." Elliott himself even called it "macho" in an interview. These words work as a description of cathartic music, but they're not really adjectives for the kind of guy I'd want to hang out with at a party. The point being, those adjectives are also ways to describe a man. The analogy I'm creating is that the sound represents a masculine identity.

So, now imagine Elliott, 18 or 19 years old, trekking across the country from Oregon to Massachusetts to go to Hampshire College. At this point he's already thinking about his identity, because he changed his name from Steven to Elliott. In an interview, he apparently said this about his birth name, "there's no good versions of it, ya know like there's, Steven...Steven is like sort of too . . . bookish. Steve is like...like jockish, sorta. Big handsome Steve, big shirtless Steve, ya know, like football playin' blond haired Steve. Ya know? I didn't like it." He met Neil Gust, who would become the other singer and guitarist in Heatmiser, and the two would go to open mics and play acoustically. The thing is: Hampshire College's campus is smack dab in the middle of the state, between Boston and Northampton. These were big music regions where post-punk and hardcore were flourishing at the time.

It’s possible that Elliott and Neil went to see bands like The Pixies or Dinosaur Jr. play in a gritty and grimy venue like Boston's legendary The Rat. Compared with "bookish" or "jockish" identities, this scene could have seemed like a path to an alternative identity through this music. The duo then started a band and when they move back to Portland after graduation, they got to be a formative part of the music scene there and eventually made the first Heatmiser album, Dead Air.

The sonic trends of the Portland music scene at the time are described in Heaven Adores You as "muscular," "loud," "angry," and "shouty." Elliott himself even called it "macho" in an interview. These words work as a description of cathartic music, but they're not really adjectives for the kind of guy I'd want to hang out with at a party. The point being, those adjectives are also ways to describe a man. The analogy I'm creating is that the sound represents a masculine identity.

So, now imagine Elliott, 18 or 19 years old, trekking across the country from Oregon to Massachusetts to go to Hampshire College. At this point he's already thinking about his identity, because he changed his name from Steven to Elliott. In an interview, he apparently said this about his birth name, "there's no good versions of it, ya know like there's, Steven...Steven is like sort of too . . . bookish. Steve is like...like jockish, sorta. Big handsome Steve, big shirtless Steve, ya know, like football playin' blond haired Steve. Ya know? I didn't like it." He met Neil Gust, who would become the other singer and guitarist in Heatmiser, and the two would go to open mics and play acoustically. The thing is: Hampshire College's campus is smack dab in the middle of the state, between Boston and Northampton. These were big music regions where post-punk and hardcore were flourishing at the time.

It’s possible that Elliott and Neil went to see bands like The Pixies or Dinosaur Jr. play in a gritty and grimy venue like Boston's legendary The Rat. Compared with "bookish" or "jockish" identities, this scene could have seemed like a path to an alternative identity through this music. The duo then started a band and when they move back to Portland after graduation, they got to be a formative part of the music scene there and eventually made the first Heatmiser album, Dead Air.

Elliott would eventually admit, "I was being a total actor, acting out a role I didn't even like," in an interview with a zine in 1997. The fact that he comes out and says he was playing a role is significant, because my analysis here is largely based on the idea that gender is a performance rather than a natural or biological state. It's a theory most notably put forth by Judith Butler, and essentially means that masculinity isn't something you are, it's something you do. It's a performance and you have to be constantly proving that your a man through your actions. So, playing macho rock in 1991 in Portland was something that was expected of guys like them. Something that would let them fit in and something that could have made them famous.

Elliott was lucky that his acting pertained mostly to music. Plenty of scenes that sounded similar to '90s Portland had a lot of problems with misogyny and violence and plenty still do. Those are the kind of acts that are dangerous for people to fall into. That's not to say that all scenes are toxic. Many of them were champions of progressive causes, which can be seen in the book Our Band Could be Your Life.

Heatmiser signed to a huge label, Virgin Records, but the band fell apart immediately after. Elliott says to Under the Radar, "I was the guy who made that gravy-train crash so to speak, and it was a gravy-train at the time." Elliott moved out of his apartment with Neil and moved in with his girlfriend, and when you read Elliott's biographies, it seems like there was a desire to put some distance between himself and his old self. That’s where he started writing new material that was slower and quieter. Again, the sound is an apt metaphor for his masculinity. He had to separate himself from normative influences in order to find himself.

Some of Elliott's friends have assumed that the recordings he did in 1994, which would end up being his debut solo album, Roman Candle, were intended to eventually be Heatmiser songs. All of Elliott's contributions on Heatmiser's last album in 1996, Mic City Sons, are more in line with his solo albums that were to follow. In Heave Adores You, the band members say that the group never really talked about things. My theory is that Elliott was trying to claim his independent identity and he felt that could no longer do that in the environment that he had been in.

Personally, I identify greatly with what Elliott went through, especially when I look back at my last.fm listening history throughout the years. In doing so, I came back to Nirvana. I've always found parallels between Elliott and Kurt Cobain. They grew up in similar times, were influenced by similar music, had similar families and careers.

Kurt's unplugged show was a huge turning point in his career, because, I think, he showed himself that he didn't have to play the aggressive, distorted rock and roll that everyone expected of him. He always had a strong pop foundation for Nirvana's music and before his death, he had made plans to record songs with Michael Stipe of R.E.M. I always wished that Kurt hadn't killed himself (conspiracy theories aside) if only so that I could've heard what his next musical direction would've been. I think he would've started putting out albums much more like Elliott's.

When I was in high school, my parents were really concerned by how obsessed I was with Kurt Cobain because of his suicide. But, that wasn't why I was interested in him. Kurt Cobain showed me that there are other ways of being. A man could go against the mainstream and advocate for things he believed in, like the way Kurt did for women's and gay rights.

It seems like Elliott figured out something similar, and he turned against his past strongly. There was clearly a conflict that Elliott had with how he felt about his work in Heatmiser. He told Under the Radar, "Sometimes I think I said, 'That band [Heatmiser] sucked,' which is really not cool. That's one of the things I regret. Since then I've talked to Neil. He understands that it's just one of those things you can't take back. It sucks. I think it hurt him for a while."

There is a line in "Between the Bars" on Elliott's Either/Or that goes, "People that you've been before that you don't want around anymore." The song is really a love song to alcohol and this line is about supressing past trauma, but it also works to understand this reflex. The clearest way to become who you want to be is to turn against everything that you had been and to bury it behind you. Before I even knew anything about Heatmiser, I always personally associated that line with my own past identities that I was embarrassed by and ashamed of and wanted nothing to do with anymore.

In all the interviews, Elliott never seems to fully understand why he decided to play that role. He says, "It was kinda weird – people that came to our shows, a majority of them were people I couldn't relate to at all. Why aren't there more people like me coming to our shows? Well, it's because I'm not even playing the kind of music that I really like." This is something that Kurt Cobain noticed as well. Eventually, Nirvana shows were full of people that Kurt said were, "the kind of guys who used to beat me up in high school" (from the book Experiencing Nirvana). The biggest irony was that Elliott and Kurt broke from the mainstream to find themselves in another kind of mainstream.

There's a huge lack of education about masculinity in American culture. The feminist movement has brought a certain sense of liberation to women, but there really isn't an equivalent for male culture. Things directed at men usually end up as a smokescreen for extreme right wing ideology, like the "men's movement" of the '60s and '70s or more recently, figures like Jordan Peterson. That makes this ignorance very dangerous and we're lucky that we have rabbit holes like Elliott Smith's music for young men to fall into.

Still even today, there's still a lot of judgement about Elliott's music. He was very conscious about how he was perceived by the media and he also wrote explicity about masculinity in some of his songs. You can check out my post here for more about that connection. None of it was easy or obvious for him. He even wrote a song that he played live a few times in 2001 called "Confusion," with the refrain "Confusion is king." Elliott had to open himself up to ridicule and he had to make sacrifices that might have damaged some of his relationships in order to find his way. But he had the guts to do it. For me, that's always been an inspiration.

Check out other posts on Elliott Smith:

A Shot of White Noise & Violent Girl |

|

|